par c.foussa Mer 12 Juil 2017 - 17:15

par c.foussa Mer 12 Juil 2017 - 17:15

9 jours avant l'incident du 787 d' ANA, avait eu lieu à Boston un incident similaire sur un 787 de JAL au parking à Boston.

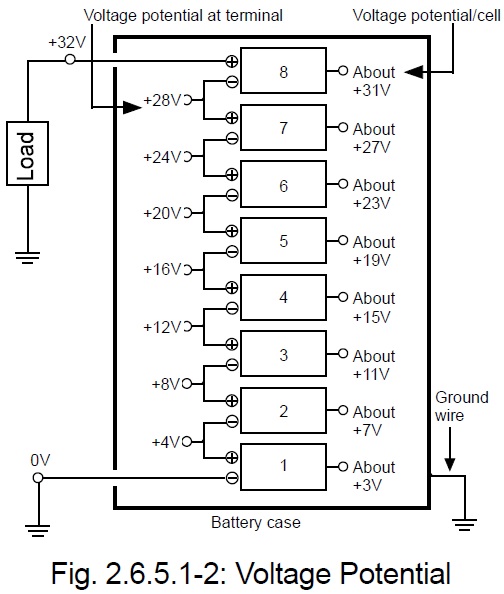

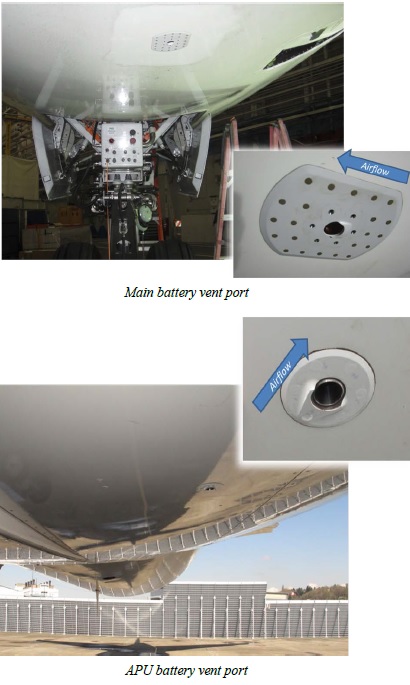

Cette fois l'incident ne concernait pas la batterie principale mais la batterie APU et qui sont identiques: même fabricant japonais (YUASA) sous le contrôle de Thales, 75 Ampere-heures (Ah) et 29.6 Volts.

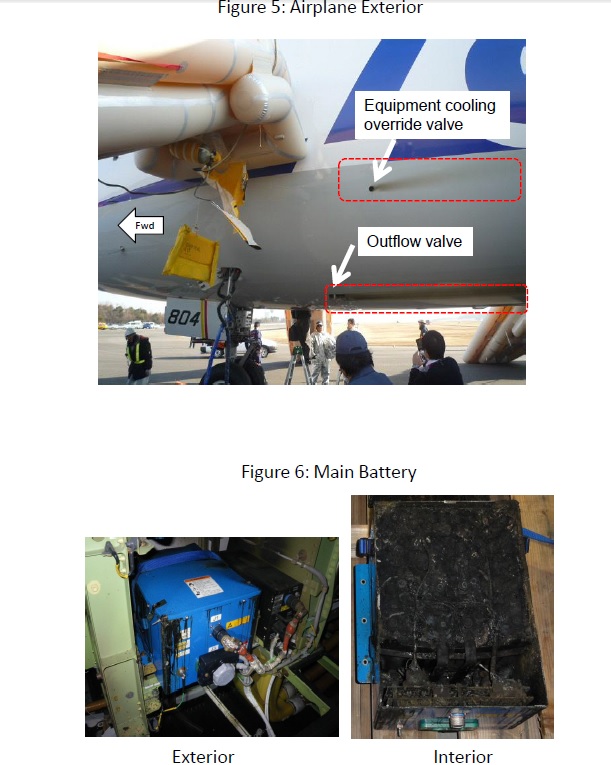

L'incident s'est produit au sol alors que l'avion était vide après le débarquement, de la fumée a été observée à l'arrière de la cabine par le personnel de nettoyage et un technicien au sol près de la porte de soute électronique arrière. En même temps, l' APU s'arrête automatiquement alors qu'un technicien est au cockpit.

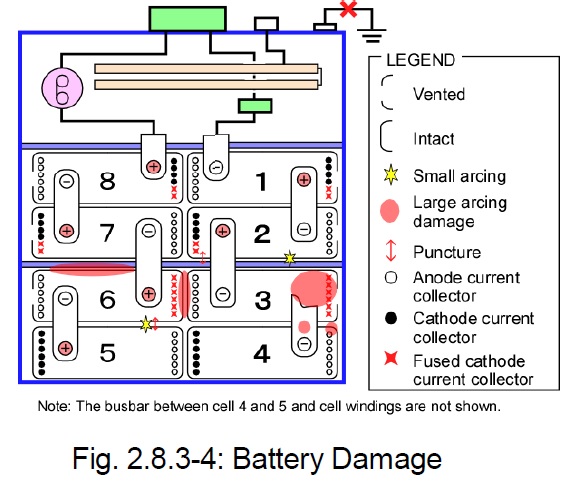

Arrivée des pompiers, ouverture de la soute, feu et fumée sur la batterie APU. Emballement thermique du au contact de 2 des 8 cellules de la batterie lithium-ion (LIB).

Le NTSB dans son rapport final a pointé 5 problèmes majeurs et un mineur relatif à l'enregistreur CVR:

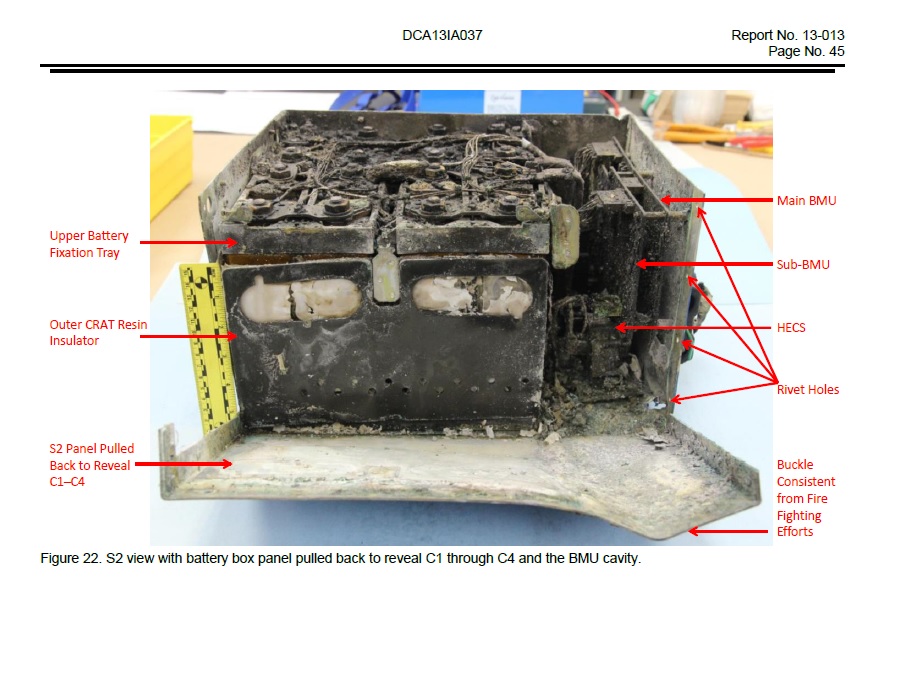

Cell internal short circuiting and the potential for thermal runaway of one or more battery cells, fire, explosion, and flammable electrolyte release. This incident involved an uncontrollable increase in temperature and pressure (thermal runaway) of a single APU battery cell as a result of an internal short circuit and the cascading thermal runaway of the other seven cells within the battery. This type of failure was not expected based on the testing and analysis of the main and APU battery that Boeing performed as part of the 787 certification program. However, GS Yuasa did not test the battery under the most severe conditions possible in service, and the test battery was different than the final battery design certified for installation on the airplane. Also, Boeing’s analysis of the main and APU battery did not consider the possibility that cascading thermal runaway of the battery could occur as a result of a cell internal short circuit.

[*]Cell manufacturing defects and oversight of cell manufacturing processes. After the incident, the NTSB visited GS Yuasa’s production facility to observe the cell manufacturing process. During the visit, the NTSB identified several concerns, including foreign object debris (FOD) generation during cell welding operations and a postassembly inspection process that could not reliably detect manufacturing defects, such as FOD and perturbations (wrinkles) in the cell windings, which could lead to internal short circuiting. In addition, the FAA’s oversight of Boeing, Boeing’s oversight of Thales, and Thales’ oversight of GS Yuasa did not ensure that the cell manufacturing process was consistent with established industry practices.

[*]Thermal management of large-format lithium-ion batteries. Testing performed during the investigation showed that localized heat generated inside a 787 main and APU battery during maximum current discharging exposed a cell to high-temperature conditions. Such conditions could lead to an internal short circuit and cell thermal runaway. As a result, thermal protections incorporated in large-format lithium-ion battery designs need to account for all sources of heating in the battery during the most extreme charge and discharge current conditions. Thermal protections include (1) recording and monitoring cell-level temperatures and voltages to ensure that exceedances resulting from localized or other sources of heating can be detected and addressed before cell damage occurs and (2) establishing thermal safety limits for cells to ensure that self-heating does not occur at a temperature that is less than the battery’s maximum operating temperature.

[*]Insufficient guidance for manufacturers to use in determining and justifying key assumptions in safety assessments. Boeing’s EPS safety assessment for the 787 main and APU battery included an underlying assumption that the effect of an internal short circuit within a cell would be limited to venting of only that cell without fire. However, the assessment did not explicitly discuss this key assumption or provide the engineering rationale and justifications to support the assumption. Also, as demonstrated by the circumstances of this incident, Boeing’s assumption was incorrect, and Boeing’s assessment did not consider the consequences if the assumption were incorrect or incorporate design mitigations to limit the safety effects that could result in such a case. Boeing indicated in certification documents that it used a version of FAA Advisory Circular (AC) 25.1309, “System Design and Analysis” (referred to as the Arsenal draft), as guidance during the 787 certification program. However, the analysis that Boeing presented in its EPS safety assessment did not appear to be consistent with the guidance in the AC. In addition, Boeing and FAA reviews of the EPS safety assessment did not reveal that the assessment had not (1) considered the most severe effects of a cell internal short circuit and (2) included requirements to mitigate related risks.

[*]Insufficient guidance for FAA certification engineers to use during the type certification process to ensure compliance with applicable requirements. During the 787 certification process, the FAA did not recognize that cascading thermal runaway of the battery could occur as a result of a cell internal short circuit. As a result, FAA certification engineers did not require a thermal runaway test as part of the compliance demonstration (with applicable airworthiness regulations and lithium-ion battery special conditions) for certification of the main and APU battery. Guidance to FAA certification staff at the time that Boeing submitted its application for the 787 type certificate, including FAA Order 8110.4, “Type Certification,” did not clearly indicate how individual special conditions should be traced to compliance deliverables (such as test procedures, test reports, and safety assessments) in a certification plan.

[*]Stale flight data and poor-quality audio recording of the 787 enhanced airborne flight recorder (EAFR). The incident airplane was equipped with forward and aft EAFRs, which recorded cockpit audio data and flight parametric data. The EAFRs recorded stale flight data for some parameters (that is, data that appeared to be valid and continued to be recorded after a parameter source stopped providing valid data), which delayed the NTSB’s complete understanding of the recorded data. In addition, the audio recordings from both EAFRs during the airborne portion of the flight were poor quality. The signal levels of the three radio/hot microphone channels were very low, and the recording from the cockpit area microphone channel was completely obscured by the ambient cockpit noise. These issues did not impact the NTSB’s investigation because the conversations and sounds related to the circumstances of the incident occurred after the airplane arrived at the gate and the engines were shut down, at which point the quality of the audio recordings was excellent.